Today, February 28th …

Today, February 28th …The one hundredth birthday edition of the Michelin guide was released on this day in the year 2000. Twenty-two restaurants were awarded the prestigious three stars – breaking what many felt was an unacknowledged limit of twenty-one to be so honoured. The guide is highly influential – some say too influential - and has certainly not been without controversy. A star more or less can make or break a restaurant, and perhaps even a life – the suicide in 2003 of Bernard Loiseau in Burgundy was said to have been triggered by the fear of loss of a star.

Finding food on motoring trips was not a problem faced by many people when the Guide Michelin began its rise to power, although excitement in the new method of transport was whipping up. The world’s first true motor race had taken place a few years earlier, in 1895. It was from Paris to Bordeaux and back, and observers were stunned when Emile Lavassor won in a mere 48 hours and 48 minutes. He stopped, they say, only at the halfway point, for a glass of champagne and a cup of weak soup. If only the guide had been available then, perhaps he would have fared better.

The alternative time-honoured way of solving the problem is to take your own food along on motoring trips. Today we prefer the convenience of ‘service areas’ over the organisation required to provision ourselves for the road, but in the early days of motoring, the packing of the picnic lunch was most important. In an article in 1914 assuring its readers that the motor car was ‘not an expensive luxury’ but ‘the vehicle of freedom’, The Times stressed the importance of thorough planning if the trip was to be enjoyable.

For economical foreign or home travel the most suitable motor-car for three or four people is a comfortable five-seated car of from 15-20 h.p., with a first-class hood fitted with side-curtains and capable of being raise and lowered from within the car. It is of the first importance that there should be ample room in the body for the extra coats, rugs, and other paraphernalia such as picnic baskets, the necessity for which is so often forgotten until the time comes for finding room for them all.

Proper planning of luggage requirements, The Times reminded its readers, would also “avoid one of the most irritating difficulties of long-distance touring, the sending forward of one’s main belongings by train.” And we could all do without that hassle, couldn’t we?

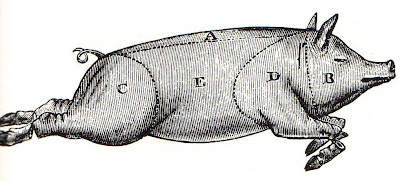

But what to put in the picnic basket? An English standby was a pie – a substantial, pie with a sturdy crust and a meaty filling. I don’t know if Lady Clark of Tillypronie went on motoring trips, but this recipe from her cookbook, published posthumously in 1909, would be just the thing for a motor excursion. It is a game pie in the grandest of pie traditions, its basic construction essentially unchanged for well over half a millennium.

Birk Hall Excursion Pie

A cold game pie.

This requires 4 grouse or 6 partridge to make a very good pie. If you take grouse, use the fillets only, and as large as you can get without bones. Make clear or thick soup of the rest of the birds. Lay the grouse or partridge fillets in the pie-dish with a sliced onion and some chopped truffles; season, and cover with first stock; then add the paste and remember to make a hole as a ‘chimney’ in the centre of the paste under the centre ornament or ‘rose’ to let out unwholesome steam.

For the paste take ½ lb. flour, 4 ozs. butter or some dripping, 1 egg, a little salt, and as much water as will make it into a stiff paste; work it well. Prepare the crust of this and put it on.

Put the pie to bake in the oven. In 1 ½ hours the paste will be a nice brown. If this is so, the pastry is done enough, but the birds will require ½ hour’s additional simmering to make them tender (i.e., 2 hours in all); so cover the paste quickly with paper to prevent its catching, and if the oven bottom is cool, as it is at Birk Hall, put the pie on that, but if it is hot (as it is in many ovens) then put the pie on the top of the hot plate, or wherever it is cool, to simmer the meat the additional ½ hour. Take off the paper and replace the ‘rose’. Serve cold for an excursion or for breakfast

Tomorrow’s Story …

How Long is a Leek?

A Previous Story for this Day …

Our story was about our old friend Samuel Pepys

Quotation for the Day …

Anybody can make you enjoy the first bite of a dish, but only a real chef can make you enjoy the last. François Minot, Editor, Guide Michelin.