Wednesday, March 02, 2011

Polite Management of the Kitchen.

Now there is a book title we are not likely to see recycled any time soon - the modern ‘good wife or tender mother’ would not find much medical or surgical advice in the modern cookery book!

The lengthy preface includes the following insights:

The Directions relating to COOKERY are Palatable, Useful, and Intelligible, which is more than can be said of any now Publick in that kind ; some great Masters having given us Rules in that Art so strangely odd and fantastical, that 'tis hard to say, Whether the Reading has given more Sport and Diversion, or the Practice more Vexation and Chagrin, in spoiling us many a good Dish, by following their Directions. But so it is, that a Poor Woman must be laugh'd at, for only Sugaring a Mess of Beans ; whilst at Great Name must be had in Admiration, for Contriving Relishes a thousand times more Distastful to the Palate, provided they are but at the same time more Expensive to the Purse.

The author hopes that the book will instruct ‘Young and Unexperienced Dames’ in ‘the Polite Management of their Kitchins, and the Art of Adorning their Tables with a Splendid Frugality.’ What a marvellous sentence, and a marvellous sentiment! Methinks the world would be a better place for the reinstatement of the concepts of polite management of the kitchen, and adorning the table with splendid frugality.

From the book, my recipe choice today is:

To Dress Hogs Feet and Ears, the best Way.

WHEN they are nicely clean'd, put them into a Pot, with a Bay-leaf, and a large Onion, and as much Water as will cover them; season it with Salt and a little Pepper; bake them with Houshold-Bread; keep them in this Pickle 'till you want them, then take them out and cut them in handsome pieces; fry them, and take for Sauce three spoon-fulls of the Pickle; shake in some Flower, a piece of Butter, and a spoon-full of Mustard: lay the Ears in the middle, the Feet round, and pour the Sauce over.

Quotation for the Day.

No one who cooks, cooks alone. Even at her most solitary, a cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past, the advice and menus of cooks present, the wisdom of cookbook writers.

Laurie Colwin.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Wick-a-what?

I found the recipe in Home pork making; a complete guide ... in all that pertains to hog slaughtering, curing, preserving, and storing pork product--from scalding vat to kitchen table and dining room (Chicago, 1900), by Albert Fulton, and I have been unable to find any other reference to it at all.

German Wick-a-Wack.

Save rinds of salt pork, boil until tender, then chop very fine, add an equal amount of dried bread dipped in hot water and chopped. Season with salt, pepper, and summer savory; mix, spread one inch deep in baking dish, cover with sweet milk. Bake one-half hour. Very nice.

It is some sort of savoury bread pudding, and does indeed sound interesting, but whence the name? I await your enthusiastic comments, wild guesses, and the fruits of you deep knowledge. In the meantime, it is an excuse to give you a favourite, but rather long, prose extract in lieu of a quotation for the day.

Quotation for the Day.

Of all the delicacies in the whole mundus edibiles, I will maintain roast pig to be the most delicate. There is no flavor comparable, I will contend, to that of the crisp, tawny, well-watched, not over-roasted crackling, as it is well called – the very teeth are invited to their share of pleasure at this banquet in overcoming the coy, brittle resistance – with the adhesive oleaginous – oh, call it not fat! But an indefinable sweetness growing up to it – the tender blossoming of fat – fat cropped in the bud – taken in the shoot – in the first innocence – the cream and quintessence of the child-pig’s yet pure food – the lean, no lean, but a kind of animal manna – or rather fat and lean (if it must be so) so blended and running into each other that one together makes one ambrosian result or common substance.

Charles Lamb.

Monday, May 18, 2009

A Law about Eating.

Needless to say, whenever or wherever they have been enacted, sumptuary laws have proven almost impossible to police, and we can be reasonably confident that the great men of Edward’s realm took little or no notice of the restrictions, and continued feasting as they had always done.

There are no early fourteenth century English cookery books known to us, so we must turn to The Forme of Cury, compiled by the Master Cooks of King Richard II in about 1390 for our recipes for today. Here are a couple of nice ideas for you – pork with sage for a “flesh” day and salmon with leeks for a “fish” day.

Pygg in sawce Sawge [sage]

Take Pigges yskaldid [scalded] and quarter hem and seethe [boil] hem in water and salt, take hem and lat hem kele [cool]. take persel [parsley] sawge [sage]. and grynde it with brede and zolkes of ayrenn [eggs] harde ysode [boiled]. temper it up with vyneger sum what thyk. and, lay the Pygges in a vessell. and the sewe onoward and

serue it forth.

Cawdel Of Samoun.

Take the guttes of Samoun and make hem clene. perboile hem a lytell. take hem up and dyce hem. slyt the white of Lekes and kerue hem smale. cole [cool] the broth and do the lekes therinne with oile and lat it boile togyd yfere. do the Samoun icorne therin, make a lyour of Almaundes mylke & of brede & cast therto spices, safroun and salt, seethe it wel. and loke that it be not stondyng [too thick].

Quotation for the Day.

Pork - no animal is more used for nourishment and none more indispensable in the kitchen; employed either fresh or salt, all is useful, even to its bristles and its blood; it is the superfluous riches of the farmer, and helps to pay the rent of the cottager.”

Alexis Soyer (1851)

Friday, May 01, 2009

Take one thousand beans ....

My time being somewhat fragmented right now (and perhaps for the next couple of weeks), the party will be cut short – although hopefully the champagne will flow freely – and you must do what you will yourselves with the following ideas.

First, the vegetables:

Here is an interesting idea: I had never heard of this plant until I came across the following recipe, from A Shilling Cookery for the People, by Alexis Soyer, 1855

Farmers in the vicinity of large towns would do well to undertake their cultivation, as they would find a ready sale in all such places. At that time of year they are in full bloom, and are called by the above singular name in consequence of the thousands of heads continually sprouting from their root. The plant covers nearly one yard in circumference, and bears no resemblance to any other green I recollect seeing, not even to Brussels sprouts.

Now, I don’t know about you, but I am disinclined to count the number of individual beans required for a dish:

The London art of cookery and domestic housekeeper's complete assistant, by John Farley, 1811

But a thousand beans is nothing compared to a thousand-weight of pork (although I have no idea what this really means – this is your homework for the week.)

Domestic cookery, useful receipts, and hints to young housekeepers by Elizabeth E. Lea, 1859

And of course no celebration is complete without dessert. I give you millefeuille (“thousand leaves”)

The housekeeper's guide, by Esther Copley, 1838

Looking forward to being with you all for the next one thousand!

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Scraps.

Wednesday, August 06, 2008

Dinner “Out West”

I have something for you just for fun today, while your system recovers from yesterday’s idea of Tomato Marshmallow. It is from a fascinating publication called Yankee Notions in 1854 – a worthy read which appears have modelled itself on the well-known English Punch magazine.

It is for those of you who love pig, or love to hate pig. It is, I am sure, entirely tongue-in-cheek, and there is, I am sure, some intended regional slur, but it is, I am certain, very amusing. And in any case, there are historic precedents for one-meat meals: Horsemeat dinners in

The Bill of Fare.

A party of our friends stopped one day, a year or two ago, at ‘Barkis’ Hotel’, somewhere “out west” and asked him to get them some dinner. “Barkis was willing” and spread before them the following bill of fare; various, “that the tastes of desultory man, studious of change, and pleased with novelty, might be indulged.”

BARKIS’ HOTEL – BILL OF FARE

ROASTED.

Pig, Pork, Ham, Hog

BOILED.

Ham, Eggs, Ham and Eggs, Hams,

BAKED.

Beans, Pork and Beans, Bread, Biscuit.

COLD DISHES.

Boiled - Ham, Roast - Swine.

Boiled - Pork, Roast -Pig

Boiled - Pig, Roast - Pork

Boiled - Swine, Roast - Ham

Cooked - Animals, Baked – Pig

Cooked - Injun, Baked - Ham

Cooked - Pies, Baked - Pork

Cooked - Cake, Baked - Swine

Cooked - Biscuit, Baked - Hog

Cooked - Beans, Baked - Beans

PASTRY, ETC.

Pie - Mince, Cake - Fruit

Pie -

Pie - Apple, Cake - Cymbals

Apples and Cheese.

LIQUORS

Monongaheel, Dark do.

McGuckin, Gin Whiskey Bill.

One of our friends tells us that he ate so heartily of some of the earlier dishes, that he had little appetite for the cold “courses!”

***

I had to take some liberties with the formatting of the 'original' menu, for those of you who are sticklers for such things - I blame Blogger. Or me.

Now, for our recipe for the day, I give you pork and dessert in one, from The Great Western Cook Book, or Table Receipts, Adapted to Western Housewifery. circa 1851.

Pork Apple Pie.

Make your crust in the usual way; spread it over a large, deep plate; cut some slices of fat pork, very thin, also some slices of apples; place a layer of apples, and then of pork, with a very little allspice, and pepper, and sugar between--three or four layers of each--with crust over the top. Bake one hour.

Quotation for the Day …

Any part of the piggy

Is quite all right with me

Ham from

Ham as lean as the Dalai Lama

Ham from

Trotters Sausages, hot roast pork.

Crackling crisp for my teeth to grind on

Bacon with or without the rind on

Though humanitarian

I'm not a vegetarian.

I'm neither crank nor prude nor prig

And though it may sound infra dig

Any part of the darling pig

Is perfectly fine with me.

Noel Coward.

Thursday, May 01, 2008

Pepys' Porke.

May 1 ...

My old friend Samuel Pepys gives me my story today, as he has done so often in the past. It was common in his time to give and receive spontaneous ‘gifts’ of food – and there are frequent mentions in his diary of the exchange of such things as haunches of venison, swans, fruit, and barrels of oysters and sturgeon. On this day in 1663 he was slightly puzzled by a gift of pork:

“This day Capt. Grove sent me a side of porke, which was the oddest present, sure, that ever made to any man; and the next, I remember I told my wife, I believe would be a pound of candles or a shoulder of mutton. But the fellow doth it in kindness and is one I am beholding to.”

I don’t know why Sam thought a present of pork was odd. Perhaps for a slightly snobby recipient it was too close to the food of peasants? On the other hand, oysters were pretty ordinary fare at that time, but Sam often gave or received quanitities of them as gifts.

Pork is quite a problematic meat. The world seems to be divided between pork lovers (and eaters) and pork haters (or avoiders). Obvious avoiders are those of the Jewish and Moslem faiths for whom pork-avoidance is a religious tenet, but there have also been some Christian groups who have eschewed it. One of the founders of the

A life without pork would be incomprehensible in many peasant cultures where a pig is the absolute backbone of the domestic economy - because even a poor household can support an animal that will not only rear itself on household scraps and foraging, but whose meat is easily and wonderfully preserved as sausage and bacon.

The digestibility and nutritional value of pork has been hotly debated by ‘experts’ throughout recorded history. The ancient Greek physician Galen, whose theories dominated Western medical thought for many centuries, thought that pork flesh was the closest to human flesh (thus legitimising the use of such things as mummified bodies for medicinal purposes right up until into the nineteenth century). The Pacific Islanders familiar to Robert Louis Stevenson referred to the human body (when used for culinary purposes) as ‘long pig’ – and they were surely not familiar with Galen, so presumably got the idea independently, and based it on its flavour?

The aesthetic paradox of the life of the pig and the value of its meat was summed up beautifully in 1745 by Louis Lémery in his comprehensive Treatise of All Sorts of Foods: Both Animal and Vegetable:

“Every Body knows, that an Hog is a nasty, filthy Creature, that delights in Mire and Ordure ; but its Flesh, as well as its other Parts, have a good Taste, and are much used for Food.”

Sadly, Sam Pepys does not indicate in his diary how his pork gift was dressed for the table. A well-known cookbook of his time was The Accomplisht Cook (1660), by Robert May, and it gives an overview of roast pork that shows us just how long sage and apple have been traditional accompaniments.

2. Mustard, vinegar, and pepper.

3. Apples pared, quartered, and boild in fair water, with some sugar and butter.

4. Gravy, onions, vinegar, and pepper.

*The ‘harslet’ (or haslet) is a less recogniseable treat in these offal-negative times. It refers to the entrails or viscera of an animal - particularly a pig, – as well as to a sort of meatloaf made from these tidbits. If you use oatmeal in the ‘meatloaf’, I guess it is pretty much the same as haggis, only without the bagpipes. Here is a recipe for you, in case you are offal-positive.

Pigs’ Harslet.

Wash and dry some liver, sweetbreads, and fat and lean bits of pork, beating the latter with a rolling-pin to make it tender: season with pepper, salt, sage, and a little onion shred fine; when mixed, put all into a cawl, and fasten it up tight with a needle and thread. Roast it on a hanging jack, or by a string.

Serve with a sauce of port-wine and water, and mustard, just boiled up, and put into a dish. Or serve in slices, with parsley, for a fry.

[A New System of Domestic Cookery: Formed Upon Principles of Economy ... Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell, 1824]

Tomorrow’s Story ..

Luncheon with the Royals.

Quotation for the Day …

As for bread, I count that for nothin'. We always have bread and potatoes enough; but I hold a family to be in a desperate way when the mother can see the bottom of the pork barrel. Give me children that's raised on good sound pork afore all the game in the country. Game's good as a relish and so's bread; but pork is the staff of life. . . . My children I calkerlate to bring up on pork with just as much bread and butter as they want. James Fenimore Cooper, The Chainbearer, 1845.

Monday, April 14, 2008

Chicken pie without the chicken.

April 14 ...

The Editor of The Cultivator – the journal of the New York Agricultural Society –made a ‘polite invitation’ to Farmers’ wives and daughters to furnish recipes for future publication in the issue of

The response must have been underwhelming, for in March, the Editor’s wife herself supplied a few recipes. This one is intriguing:

Mock Chicken Pie.

Boil common potatoes – season highly with salt and pepper; some prefer a little thyme or summer-savory. Pour milk over them, and stir till of a moderate paste; fill a pie dish with crust above and below the contents. Strew pieces of pork through it. Bake in an oven, and serve hot. A single crust, filled and doubled, is called tarn-overs.

My puzzle is this: why not call it Pork and Potato Pie?

I am moderately intrigued by the whole, old concept of Mock Food. There seem to be several reasons for counterfeiting food, but I am not sure which one applies here. The commonest reason is probably one of necessity – when a substitute must be found for either a more expensive or unavailable ingredient. Such counterfeit foods are common in times of scarcity: wartime ersatz coffee for example. Or carob for real chocolate, when there is a scarcity of common sense. This explanation surely does not apply in the above recipe? Down on the farm, when a pie is called for, a single family-size post-menopausal hen would be more easily available to substitute for a big porker than the reverse, wouldn’t it?

Deception is another reason. The family want chicken pie, but there is still some leftover roast from Sunday which must be used up? They say they hate pork but it was cheap this week at the market?

The other issue of importance is : was this pie intended to be served up as if it was chicken, with the truth not told?

The third reason for making mock food is for fun: meatloaf with slivered almonds stuck all over it and called hedgehog, for example. But there is nothing remotely hilarious about the mock-chicken pie, is there? Or am I am missing something?

It seems that this topic of mock food is worthy of pursuing this week, as we search for enlightenment. Your input is humbly requested.

Tomorrow’s Story …

Mock Food No. 2

Quotation for the Day …

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

Dinner to die for.

October 23rd

There were in fact two levels of “invitation” - 17 guests were invited to take part, but a further 300 were to be spectators. After an elaborate checking of their credentials by guards, and the correct answering of the question “are you visiting Monsieur de la Reyniere, the opressor of the people, or Monsieur de la Reyniere, the defender of the people ?”, guests were taken to an ante-room where they were “judged” as to their merits. They were then led by Grimod first into a completely dark room (just long enough to get a little nervous) and then to a taper-lit room draped in black, with incense wafting about and a grand central funeral catafalque. Some descriptions say that there was a coffin behind each guest’s chair, and indeed, it is difficult to know for certain what is truth and what is embroidery. The three hundred spectators watched the proceedings from the balcony, and were probably grateful that they had not received the more prestigious invitation to actually participate.

There are a lot of theories as to Grimod’s motives: if he was intending to embarrass his parents (the antagonism was mutual) or annoy his guests (whom he had locked in so they could not escape), he succeeded. Alternatively he may have been making a pre-Lenten statement about the proximity of death when we are in life (an ancient theme), or he may have been paying homage to a recently deceased paramour (or would-be paramour). He may have simply wanted to play a practical joke.

It is most frustrating that no menu for this dinner survives: the food was “self-service” from side-tables, and there was, apparently, plenty of pig and oil. That is all we know. Where history leaves off however, literature comes to the rescue. Grimod’s dinner was used as inspiration for a similar event by a character in the novel Against the Grain, by J.K.Huysmans in 1884. The character in the book, called Des Esseintes, is also an eccentric known for his parties, and he hosts this particular event in memory of his (temporarily) lost virility. All the décor is black, the outside garden also being strewn with charcoal; the tablecloth is black, and the plates black-rimmed; the food is served by naked negresses. Between them, Des Essientes and his creator come up with some good ideas for an “all black” menu.

“ … turtle soup, Russian black bread, ripe olives from Turkey, caviar, mule steaks, Frankfurt smoked sausages, game dished up in sauces coloured to resemble liquorice water and boot-blacking, truffles in jelly, chocolate-tinted creams, puddings, nectarines, fruit preserves, mulberries and cherries. The wines were drunk from dark-tinted glasses, - wines of the Limagne and

It seems appropriate today to give a recipe for pig, from Grimod’s time.

To make a Ragout of Pork Chops.

Cut a loin of pork into chops, and stew it with a little broth, a bunch of sweet herbs, pepper, and salt: have ready a veal sweetbread, parboiled, and cut into large dice; put it into a stewpan, with mushrooms, the livers of any kind of poultry, and a little butter; set it over the fire, with a little flour, a glass of white wine, some gravy, and as much broth, adding salt and whole pepper, a bunch of parsley, scallions, a clove of garlic, and two cloves; let the whole boil, and reduce to a strong sauce, and serve it over the chops: or do the chops in the same manner as the ragout, and when half done, add the sweetbread, livers and mushrooms.

[The French family cook; Menon; 1793]

Tomorrow’s Story …

Devil’s Dung Sauce.

Quotation for the Day …

Everything in a pig is good. What ingratitude has permitted his name to become a term of opprobrium. Grimod de la Reyniere.

Monday, October 15, 2007

Advice for the Melancholy.

Today, October 15 ..

Firstly ….

Before I tell you today’s story, I want to make a little announcement. Small changes are afoot on this blog. I may move away, a little, from the strict “on this day” format (don’t worry, there will still be a story every weekday.)

There are two reasons. One – the negative one – is that I am aware that another blog is systematically stealing my content on a daily basis, with no acknowledgement (I think it is called a “scrapping”). So - if you are reading this and the name The Old Foodie is not at the top of the page, then you are reading this on the site of a word thief. My blog is almost two years old. As the weekend days become weekdays in each succeeding year, if I continue this format by the end of another twelve months I will have covered all 365 days. It is still my hope that I will publish something along the lines of a Food History Almanac in the future, and although I have ample more material for every day of the year, it has been suggested to me that I may be giving away potentially the entire content for such a book to some other thief.

I might add that this person is doing the same thing to another blogger who runs a site called The Art of Drink. By all means go there and say hello to Darcy, who alerted me to the theft and is also trying to get this guy to cease and desist. And no, I am not going to give you the thief’s site address, because if you go to it you will assist him to earn money from the Adsense ads he is running. At this point in time the perp has been notified to the Google Adsense team knee-capping department (at least, I hope that’s one of their disciplinary techniques.)

The second reason for the change – the positive one, I hope – is that there are a lot of lovely stories that do not have a specific date, but do not deserve to be neglected on that account. This applies particularly to the more ancient stories. So, for a little while, or from time to time, I will just give you a random story. It also means that if you have a particular question or idea, then that just might be able to be accommodated too.

And Finally, our story for the day ...The idea that food can affect mood is far from new. The ancient Greek Doctrine of the Humours underpinned medical thought until well into the Middle Ages, and it was firmly based in food as medicine and medicine as food and food as potentially mind-altering (and it was not referring only to a certain variety of mushroom). A gross over-simplification of the complex concept that was Humoral Theory goes something like this:

Everything in the natural world is made up of the four elements: Fire, Earth, Water, and Air. Each of these has a particular “quality”: fire is hot, earth is dry, water is moist, and air is cool. A combination of two of these elements gives each natural thing or process its “complexion”, which has an associated “humour”. The four humours are represented in humans by blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile (or choler). A persons “temperament” depends on which humour has “sovereignty”, so there are four basic temperaments:

SANGUINE: complexion is “hot and moist”, blood is the dominant humour.

PHLEGMATIC: complexion is “cold and moist”, phlegm is the dominant humour.

CHOLERIC: complexion is “hot and dry”, yellow bile is the dominant humour.

MELANCHOLIC: complexion is “cold and dry”, black bile is the dominant humour.

Disease was believed to be due to an imbalance of the humours, which is why it was perfectly logical to perform blood-letting if the condition was understood to be due to an excess of that particular humour, or of administering purges or diuretics for other excesses. Alternatively, deficiencies in a particular humour could be addressed by administering a medicine or food which was rich in that humour.

The system was of course more complicated, with varying “degrees” of a quality being assigned to a food, the influence of age, gender and a multitude of astrological and occult influences also having to be taken into account.

To return to our specific topic of the day, first, the diagnosis: a melancholy person could be recognised by these physical signs: digestion slowe and yll, tymerous and fearefull, anger longe and frettynge, seldome laughynge,pulse lytell, urine watry and thynne.

Secondly, the treatment: this was two-pronged. Foods with similar characteristics (i.e that were “cold and dry”) should be avoided, and foods that were “warm and moist” should be eaten. This refers of course to the actual complexion of the food, not its cooking and serving method.

So, if you are of a gloomy temperament, or are in a sad mood, the foods to avoid because they ingendre melancholy are:

Biefe

Gotes flesshe

Hares flesshe

Bores flesshe

Salte flesshe

Salte fysshe

Coleworts

All pulses except white peason

Browne breadde course

Thycke wyne

Black wyne

Olde Cheese

Olde flesshe

Great fysshes of the see.

As to what to eat, that is proving slightly more complicated for me to advise you. Pork is certainly “hot in the first degree”, so should be good, but I have not been able to find out if it is “moist” enough from a humoral point of view to be suitable for a melancholy person. From a culinary point of view it would certainly be wonderfully moist cooked according to this sixteenth century recipe, if you follow the instructions and use the recommended good store of butter. It is cooked in a pastry “coffin” which functioned like a casserole dish.

To bake a Pigge.

Take your Pig and flea [skin] it, and draw out all that clean which is in his bellye, and wash him clean, and perboyle him, season it with Cloves, mace, nutmegs, pepper & salt, and so lay him in the paste with good store of Butter, then set it in the Oven till it be baked inough.

[A book of cookrye Very necessary for all such as delight therin.1591]

Tomorrow’s Story …

The virtues of coffee.

Quotation for the Day …

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

Recipes from Scutari.

Today, June 26th …

Today, June 26th …Alexis Soyer was a famous French-born chef in Victorian England who cooked for aristocrats and gentlemens clubs, and achieved celebrity status in his own time. He was also famous for his philanthropic works in

Soyer volunteered to go to the

Here is an extract for his letter published on this day in 1855.

To the Editor of the Times,

Sir,- I herewith beg to forward you some of the most important receipts which I have concocted out of the soldiers’ rations, and which are now adopted in various parts of the camp, and will no doubt shortly be extended to every regiment in the Crimea, having had them printed for circulation throughout the army. Some of the receipts were printed at head-quarters and issued for distribution. The reason for my return to Scutari for a short time is to place a civilian cook who understands his business in each hospital, which cannot fail to be beneficial to the patients, and by a due organisation in those departments economy will in the end be effected.

I brought with me from head-quarters 12 complete rations as given daily to the troops, and with these provisions I am now teaching ten of those very willing fellows who were originally engaged as cooks in the hospitals the plain way of camp cookery, and, instead of being almost useless, as they were, in so important a branch, they will now turn out, if not the bravest in the army, at least the most wonderful, being able to face both fire and battery when requisite.

With the highest consideration, I have the honour to be, Sir, your most obedient servant,

A. SOYER

(Receipt No. 1) Stewed Salt Beef And Pork A La Omar Pasha

Put into a canteen saucepan about 2lb of well soaked beef, cut in eight pieces; ½lb of salt pork, divided in two, and also soaked; ½lb of rice, or six tablespoonsful; ½lb of onions, or four middle-sized ones, peeled and sliced; 2oz of brown sugar, or one large tablespoonful; ¼oz of pepper, and five pints of water; simmer gently for three hours, remove the fat from the top and serve. The first time I made the above was in Sir

(Receipt No. 7) Cossacks’ Plum Pudding

Put into a basin 1lb of flour, ¾lb of raisins (stoned, if time be allowed), ¾lb of the fat of salt pork (well washed, cut into small dies, or chopped), two tablespoonsful of sugar or treacle; add a half pint of water; mix all together; put into a cloth tied tightly; boil for four hours, and serve. If time will not admit, boil only two hours, though four are preferable. How to spoil the above:- Add anything to it.

Tomorrow’s Story …

A pot of the best tea.

Quotation for the Day …

An old-fashioned vegetable soup, without any enhancement, is a more powerful anti carcinogen than any known medicine. James Duke M.D.(U.S.D.A.)

Thursday, February 08, 2007

First, Kill your Pig.

The eighteenth century English country parson James Woodforde enjoyed a comfortable living from his curacy in Norfolk. The small holdings attached to his position made his household virtually self-sufficient, and the diary he kept for four decades is rich with detail of village and rural life of the time. He recorded anecdotes about harvesting, pig-rearing, fishing, bread making, preserving, and all manner of other farm and domestic duties. His dinner on this day in 1792 was “boiled Leg of Pork and Peas Pudding, a rost Rabbit and Damson Tarts”, and we can be confident that he knew intimately the source of every ingredient.

What an idyllic life! Producing one’s own natural, organic food in the peace of the countryside, completely in rhythm with the seasons. Fresh, wholesome produce. No added food miles. Simple, healthy, and stress-free.

Unless you are queasy about actually murdering your own sweet, fat little piglet with your own hands of course.

Unless you have no clue as to how to choose a good piece of fresh pork if you are unable to kill your own - thereby risking falling victim to an unscrupulous butcher trying to off-load stock from his unrefrigerated shop.

Unless you are (Heaven forbid!) lacking in that skill essential to well-bred men – skill at carving efficiently and elegantly – thus rendering yourself “disagreeable and ridiculous to others”.

Unless you have a terrible craving for lamb, but it is out of season, and anyway you have to keep eating that damned pig you killed a few days ago, even though you are sick of the sight of pork, because there is a lot left and it won’t keep much longer.

Luckily, there are plenty of eighteenth century manuals to help you, should you decide to take up this idyllic lifestyle.

A book with the instantly reassuring title of The ladies’ library: or, encyclopedia of female knowledge, in every branch of domestic economy ... In which is included a vast fund of miscellaneous information (1790) begins the recipe ‘To Roast a Pig’ with the instruction: ‘Stick your pig just above the breast-bone, running your knife to the heart; when it is dead, put it in cold water for a few minutes, then rub it all over with a little rosin beat exceeding fine and its own blood …’. So now you know how to perform that little duty.

If you are forced to obtain your pork from the market, John Trusler gave plenty of advice in his book The honours of the table, published in 1788.

Pork.

If it be young, in pinching the lean between your fingers, it will break, and if you nip the skin with your nails, it will dent. But if the fat be soft and pulpy like lard, if the lean be tough, and the fat flabby and spungy, and the skin be so hard that you cannot nip it with your nails, you may be sure it is old.

To know fresh-killed pork from such as is not, put your finger under the bone that comes out of the leg or spring, and if it be tainted, you will find it by smelling your finger; the flesh of stale pork is sweaty and clammy, that of fresh killed pork, cool and smooth.

Trusler gave advice for carving the roast meat too, and as his book was especially addressed to young people, he gave several pages of advice on how to behave at the dinner table. Methinks we modern folk could learn a little from our ancestors in this regard, so as a refresher I pass on a few tidbits of his advice:

Eat not too fast or too slow.

Spit not on the carpet.

Smell not your meat when eating.

Offer not another your handkerchief.

Not to seem indelicate here, there is a final point of etiquette which I think is very poorly attended to these days, so I am grateful to John T for reminding us:

‘If the necessities of nature oblige you at any time, (particularly at dinner,) to withdraw from the company you are in, endeavour to steal away unperceived, or make some excuse for retiring, that may keep your motives for withdrawing a secret; and on your return, be careful not to announce that return, or suffer any adjusting of your dress, or re-placing of your watch, to say, from whence you came. To act otherwise, is indelicate and rude.

Finally, to avoid a very inelegant temper-tantrum over the lamb instead of pork issue, I give a recipe from the Ladies’ Library manual of 1790, quoted from above:

To roast a Hind-quarter of PIG in Lamb-fashion.

At the time of the year when house-lamb is very dear, take the hind-quarter of a large roasting pig, take off the skin, and roast it, and it will eat like lamb, with mint sauce, or with sallad or Seville orange. Half an hour will roast it.

Have fun.

Tomorrow’s Story …

Cornbread for Hard Times.

A Previous Story for this Day …

“What Does ‘Cooking’ Mean?”

Quotation for the Day …

To do the honours of the table gracefully, is one of the out-lines of a well-bred man; and to carve well, as little as it may seem, is useful to ourselves twice every day, and the doing of which ill is not only troublesome to ourselves, but renders us disagreeable and ridiculous to others. Lord Chesterfield.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Pig, with Onions.

Today, December 21st …

Today, December 21st …There are many reasons to celebrate today, all linked somehow with the Solstice – one of the two turning points of the seasons when the sun appears to stand still, an event of special significance, so an excuse for special food. The December solstice (Winter in the Northern hemisphere, Summer in the Southern) occurs on the 21st or 22nd of the month. This year it is technically tomorrow, the 22nd (at 10:24 am AEST), but we will consider it today because this day is also old St. Thomas’ Day and the usual blend of traditions pagan, Christian, and secular overlap.

Whatever food we chose for our solstice celebrations, we are guaranteed a calm setting in which to enjoy it, for the solstice falls in the middle of the Halcyon Days. These are the fourteen days of calm seas and mild weather which supposedly fall equally around the solstice, thanks to a mythical Greek bird, the ‘alkyon’ which caused these fine conditions in order to hatch its brood on its floating nest.

Of course the fine weather prediction applies to the winter solstice, where the legend originated. There does not seem to be a corresponding guarantee in the Southern hemisphere, which about sums up our problem Down Under. All of the ‘traditional’ December solstice foods are winter foods, and many of us expect to be sweltering in the heat. I will therefore offer two alternative food themes for the day.

St. Thomas’ Day is “good for brewing, baking and killing fat swine” – in other words, household activities entirely suitable for the official beginning of winter. In Bavaria the tradition is particularly strong, and the swine is even called the “St Thomas Pig”. It is believed that if you eat well on this day you will eat well all year. This shortest day of the year is also the traditional day to plant onions and broad beans – on the basis that they will grow with the days and be ready to pick at the summer solstice.

It would seem appropriate then to give you a suitably rural, porky, oniony recipe for this day. Who better to supply this than the good eighteenth century husbandman William Ellis who ensures that nothing is wasted of the pig? The following recipes are from his book ‘The Country Housewife’s Companion’ (1750)

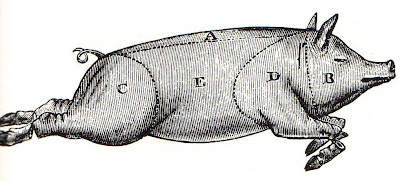

To bake the Ears, Feet, the Nose-part, Mugget, or gristly lean Parts of a Hock of Pork.

These, or any part of them, may be made a good family pleasant dish, thus: - Lay them in a glazed earthen pot, and strew over them some salt, pepper, onions, one or more bay leaves; over these pour water till it is above them, bake it two or three hours, and keep it as it comes out of the oven till wanted, then cut and fry it in slices; the sauce is a little of the pickle, flower, and butter melted with some mustard.

The Farmers Way of dressing a Porker's Head, Feet, and Ears.

We make no more to do, than to boil them tender, and eat them with mustard; and if any of them are left cold, we fry them in lard with some onions, and eat with mustard. - Or else, mince the flesh of them, and lade butter over it for eating. - But to eat the feet and ears in a nicer manner; when they are boiled, chop them small, and mix butter with gravey, shalot, mustard, and slices of lemon; then stew all together.

And for the Southern hemisphere Summer Solstice, I break with the tradition of giving you something historic and instead give you my personal recipe for Summer Solstice Cake – light and bright with sunny red, orange and yellow fruits, and fragrant with liqueur. It is a variation of my Chocolate Alcohol Christmas Cake, which I must therefore give you first.

CHOCOLATE ALCOHOL CHRISTMAS CAKES.

1650 gm dried fruit.

1/3 cup honey or golden syrup.

1 cup alcohol of your choice (choc or choc-orange liqueur is good, whisky or brandy or rum)

shredded or grated rind of one orange and one lemon

100gm (at least) of good quality chocolate, chopped up.

125 gm of nuts, if you wish. Pecans are good.

2 cups plain flour

1 cup self-raising flour

¼ cup cocoa (good quality Dutch, or Callebaut choc powder is great)

250 gm butter (NO substitutes, good cake needs good butter)

300 gm dark brown (or black) sugar

6 eggs.

Mix the fruits, honey, alcohol, and rinds in a big jar, and marinate as long as possible.

When you are ready to make the cake, sift together the flours and cocoa.

Beat together the butter and sugar until creamy, then beat in the eggs one at a time.

Fold the fruit mixture, the chopped chocolate, and the nuts into the creamed mixture, then fold in the dry ingredients in 2 batches.

Put in the greased tins, decorate the tops with cherries and nuts if you wish.

This makes one 24 cm cake PLUS 6 small cakes made in LARGE muffin tins, or make all small ones.

Time to cook: the small cakes about 1 hour at 120 degrees Celsius, the large one 3 ½ to 4 hours.

SUMMER SOLSTICE CAKE.

Make it as above, but instead:

Use all red and yellow fruits – dried cranberries (better than glace cherries I think), chopped dried apricot, peach, pear; crystallised ginger; the pale yellow sultanas.

Use a fruity liqueur – I used peach Schnapps in 2005, because that’s what I had - and it was fantastic, but Grand Marnier or Curacao would be good.

Add 1 teaspoon of vanilla extract.

Use white sugar (vanilla if possible)

No cocoa, use an extra ¼ cup plain flour instead.

Substitute white chocolate of course.

Macadamia nuts (slightly roasted first) instead of pecans.

Pour more of the alcohol of your choice over the cakes as they are cooling, and as often afterwards as you can, until time for eating.

Tomorrow’s Story …

A Food Facts Quiz.

A Previous Story for this Day …

Ortolans were featured in our story of this day in 2005.

Quotation for the Day …

It's probably illegal to make soups, stews and casseroles without plenty of onions. Maggie Waldron, American author.