Today, June 30th …

Today, June 30th …If you were passing through Glasgow, Scotland by train on this day in 1898, you might have partaken of this luncheon at the Central Station Hotel:

Table d’Hote

Luncheon menu 3/-

Green pea soup Consommé à la Brunoise

Trout, Hollandaise Sauce Fried Fillets of Sole

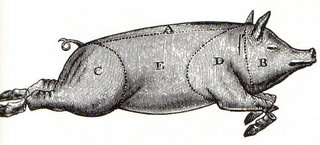

Chops Haricot Chops Steak

Cold Roast Beef Chicken and Ham

Cold Chicken and Ham Pie

Pressed Beef Tongue Galantine

Fig pudding Strawberry Ice

Gooseberry Fool Cold Tarts Jelly

STRAWBERRIES and CREAM 1s

Tomato, Beetroot, Potato, and Lettuce Salads

Cheese, Butter, etc.

Eggs en Casserole, Savoury Omelette

Devilled Shrimps, Cavaire[sic], charged extra.

Dessert 1/- Extra

At first glance it seems surprising that there are no obviously Scottish dishes on the menu - no haggis, no cock-a-leekie soup, no oatcakes. It was, however, already the goal of most hotels with any pretensions at all (and this was the "Largest and Most Luxurious Hotel in Scotland") to have a menu from which it was completely impossible for the tired traveler to determine which country or city he was currently in. Frequent travelers will be familiar with the dilemma (“It was the Consommé à la Brunoise, we must have been in Glasgow … ”).

A little book written by the Principal of a Glasgow Cookery school of the time, Mrs. Black, called “Choice Cookery: La Bonne Cuisine.” reflects this generic approach to food. There are a couple of token recipes for traditional Scottish dishes, but it could just have easily have been a manual for the Central Station Hotel chefs, rather than the housekeepers and cooks of the middle class households for whom it was intended.

There is one particularly amusingly named recipe in this book, which would have been my pick for the house specialty.

Billiard Eggs.

¼ lb Bread-crumbs; 1 oz. Butter; 1 tea-spoonful Parsley; 1 onion; 1 large mushroom; 1 Egg; A little Milk; Salt, Pepper, and Nutmeg.

Put the bread-crumbs in a basin, and add to them the parsley, which must be very finely chopped; the onion, which must be boiled, and then chopped very finely; the butter, which must be melted; and stir all very well. Then chop up the mushroom very finely, and add it; add also ¾ tea-spoonful of salt, ¼ tea-spoonful of pepper, a little nutmeg; beat up the egg and stir it in.

If necessary, add a little milk to moisten the whole. It should be just moist.

Roll this mixture into round balls. Beat up an egg and brush them over with it; roll them in fine bread-crumbs, and fry in smoking hot fat.

On Monday: The end of the Auk.

Quotation for the Day …

A soup so thick you could shake its hand and stroll with it before dinner . Robert Crawford, From his poem "Scotch Broth":