Today, September 29th …

Today, September 29th …It is Michaelmas Day today, the feast day of St Michael and All Angels in the Christian calendar, and we started our preparations yesterday. Today, after it is blessed, you may eat the Struan-Micheil that you baked yesterday.

I forgot to remind you last Sunday to pick your carrots (preferably wild carrots) in readiness for today. You should (if you are female), on the Sunday preceding Michaelmas, have gone out with your 3-pronged mattock (representing St Michael’s trident), dug some triangular holes (to represent his shield), carefully removed the carrots, tied them with a triple thread of red yarn, and presented them to visitors on this day. If all else fails there is always the market.

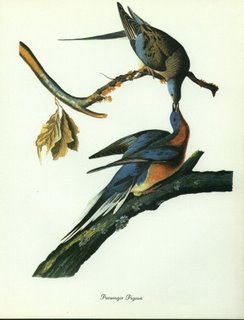

Presumably you have put a few of your carrots aside to eat with your traditional dinner today, which of course is goose. The association with goose and Michaelmas is a very long one. Geese are fat from grazing the harvest stubble at this time of year, and in any case most livestock had to be culled before the onset of winter, so serendipity has something to do with it. Michaelmas was one of the old “quarter days” of the rural calendar, the four days in the year when rents and tithes were due and servants were hired or paid, and many agreements specified livestock such as goose as payment. The tradition is clearly NOT due – and will never be due, no matter how often the story is repeated - to Queen Elizabeth I being in the process of eating goose on this day when she heard of the defeat of the Spanish Armada, for the very good reason that that particular event happened in July. Got it?

P.S The “fallaid” that you saved from the baking of your Struan-Micheil yesterday is to be sprinkled ceremoniously on your sheep and land as a harvest blessing to ensure health and good crops in the coming year.

Recipe for the Day …

Naturally we have to have a goose recipe today, and whereas sage and onion the best known traditional accompaniments, apples are also popular because (in the Northern Hemisphere, where these traditions originate) it is also apple harvest time. The recipe today uses apples, and also keeps loyal to the Scottish theme. Here follow the instructions “to smother green geese” From Scotland’s first cookbook – Mrs McLintock’s “Receipts for Cookery and Pastry-Work”, published in 1736. Be not alarmed, it is not a method of slaughtering green-feathered animals, or disguising decomposing flesh, “green” in this context means young and fresh.

To smother green Geese.

Take a young fat Goose, fill their belly with butter, Apples, Cinnamon and Nutmeg, sew up their belly, and boil her in strong broth, then coddle two Dozen of large Apples, pare them, and take out the core, beat them well with Sugar, Cinnamon, and a little fresh butter and white Wine, when the goose is well boiled, lay her in the Plate, and put the Apples over her.

Monday’s Story …

Gruel, Broth, and Bread.

Quotation for the Day …

He who eats goose on Michaelmas day

Shan't money lack or debts to pay.

[Old English Saying]